Steven Spielberg‘s Schindler’s List (1993) centers around Oskar Schindler, a man who saved over 1,000 Jewish individuals during the Holocaust. While the film briefly mentions his wife, Emilie, it doesn’t delve into her life following World War II. It’s surprising to discover, then, that a bankrupt Schindler abandoned his life partner after they fled to Argentina.

Moving to Argentina following World War II

After the Second World War, Oskar and Emilie Schindler lived in Regensburg, Germany. In 1949, they immigrated to Argentina, settling in Buenos Aires. Supported financially by a Jewish organization in the country, they worked as chicken farmers.

Emilie, who’d grown up in a small farming community in Czechoslovakia, quickly adapted to the rural lifestyle. According to her memoir, When Light and Shadow Meet, the same couldn’t be said for her partner. “I could never count on help from Oskar, who seemed more interested in the adventures the capital could provide,” she wrote.

As such, for nearly eight years, she ran their poultry farm almost entirely on her own, without her husband’s assistance.

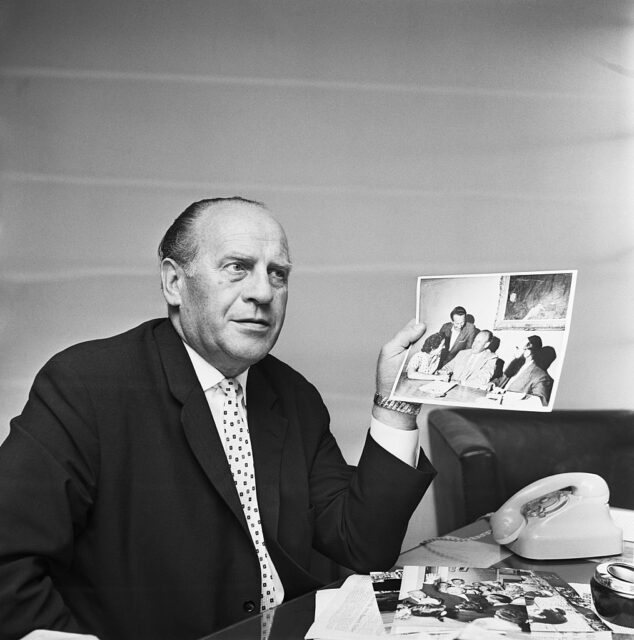

Oskar Schindler abandoned his wife in Argentina

In 1957, Oskar Schindler left Argentina for Germany, never returning. Emilie remained.

He returned because the German government had enacted a law providing reparations to victims of World War II who’d suffered the loss of property, capital or profession during the conflict. Schindler hoped to receive financial compensation for his business losses and promised Emilie he’d return to South America once the financial arrangements were completed.

However, Schindler never went back to Argentina, or to his wife. He ultimately remained in Germany, dying penniless and almost completely unknown in October 1974.

Emilie Schindler never divorced her husband

Despite Oskar Schindler not returning to Argentina or seeing Emilie again, the couple never officially divorced. The latter often considered divorcing her husband, to escape his “lies, his repeated deceits, and constant insincere repenting.” Despite this, they remained separated for the rest of their lives.

Following the release of Schindler’s List, Emilie told a German reporter that her “wedding ring was good insurance against the claims of his many mistresses.”

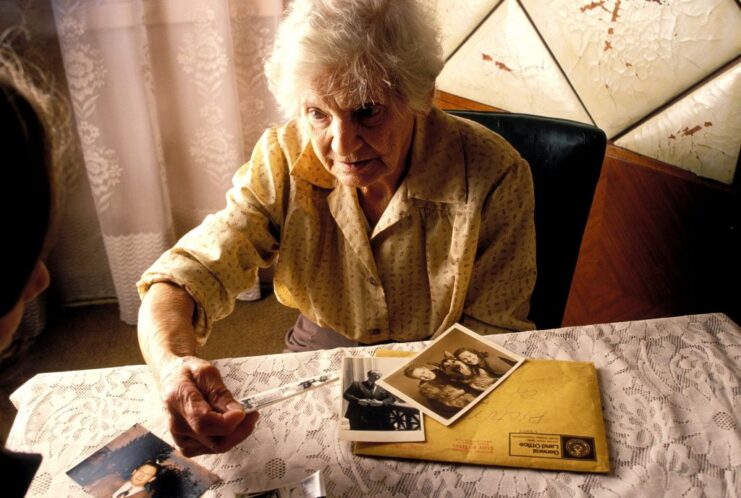

Financially struggling after Oskar Schindler left Argentina

Emilie Schindler faced significant financial struggles after Oskar’s move to Germany. According to her biography, she was unable to afford to pay her farm workers and barely had enough to feed herself. She recalled her meals primarily consisted of “tangerines I picked in the orchard, some bread, and lots of coffee to keep me awake.”

Fortunately, in 1963, Emilie began receiving a small pension from Israel and Germany, which allowed her to support herself until her death.

Emilie Schindler positively viewed Steven Spielberg’s movie

In 1993, Emilie traveled to Israel for the epilogue of Schindler’s List. In it, she, along with many of the Jewish people she and her husband had saved during the Second World War, visited Oskar Schindler’s grave. This was the only time she ever visited it.

Emilie recalled that, during her visit, she silently said to him, “Well Oskar, at last we meet again… I have received no answer, my dear. I do not know why you have abandoned me… [but] I have forgiven you everything.”

Emilie ultimately appreciated Schindler’s List, calling it “an excellent film that deserves all the awards it has received.” Her only criticism was that the film didn’t fully capture the extent of her husband’s womanizing, as she experienced it.

Recognized for her work during World War II

In 1993, Yad Vashem awarded Oskar and Emilie Schindler the title of Righteous Among the Nations, in recognition of their efforts during the Holocaust. Emilie’s memoir suggests that she played a more significant role in saving Europe’s Jewish population than is commonly understood. In a 1999 interview, she said, “Oskar is a hero. And what about me? I saved many Jews too.”

Her memoir also portrays her husband as both a womanizer and as self-serving as he was generous.