During the Vietnam War, 108 Australian soldiers stood against some 1,500 to 2,500 Vietnamese forces near the village of Long Tan. When the battle was over, the Australians had lost 18 men, while another 24 were wounded. The Vietnamese, however, may have suffered well over 500 casualties.

Although the Australians won against overwhelming odds, however, their government was quite stingy about handing out awards.

In 1965, Australia already had a presence in Vietnam, but under US control. The 1st Royal Australian Regiment (RAR) had served as the 3rd Battalion of the American 173rd Airborne Brigade, which created tensions. Wanting greater control, Australia sent over a Task Force on 14 June 1966. These joined up with the 1st RAR after having seen action in Malaya.

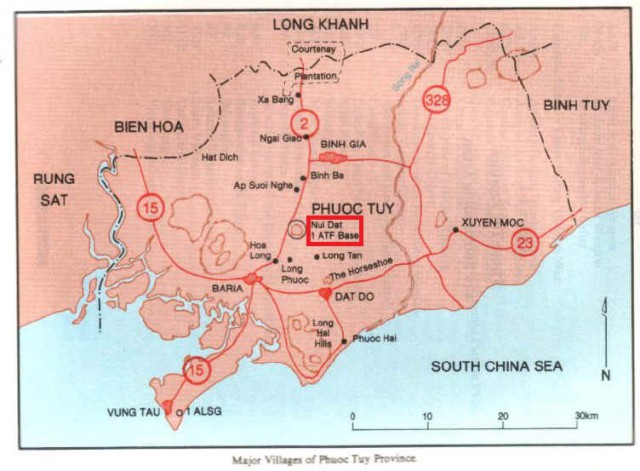

A major point of contention was that the Australians were not used to the attrition warfare that Americans preferred. Believing that the guerrilla tactics they had mastered in the jungles of Malaya would be more efficient, they set up base in the province of Phuc Tuy because it was a well-known Viet Cong stronghold.

The RAR arriving at Tan Son Nhut Airport in 1966.

Phuc Tuy also had a port that would allow them to ship troops in and out. And after a reconnaissance of the area, it was decided that the terrain would be ideal for the veterans of the Malayan Campaign.

The site they chose was at Nui Dat, a hill that commanded the center of the province. Its location ensured that if the VC wanted to get to the rest of the populace, they would first have to pass through the Australian position.

The Australian base at Nui Dat in Phuc Tuy Province.

In charge of the Task Force was Brigadier David Jackson. To secure their position and to ensure they knew friend from foe, Jackson imposed a 4,000-meter exclusion zone around the base called Line Alpha.

This meant expelling all the locals within the zone so that if they did encounter any Vietnamese, they’d know they were dealing with the VC. And to make sure the residents stayed out, all villages within the exclusion zone were destroyed.

By August 1966, the base was barely three months old and still not entirely readied. Knowing this and hoping to dislodge this very inconveniently located enemy base the VC attacked.

Site of the battle in 2005.

The Australians had picked up VC radio transmissions, but sweeps of the surrounding area found nothing. Just before midnight on August 16, Nui Dat was attacked by mortar fire and recoilless rifles. The Australians responded with counter-battery fire. The firing continued till the next morning then stopped.

The location where the VC had fired from was discovered by a sweep of three companies. Though abandoned, they did find clothes and blood stains, proving that their return fire had hit some targets.

The Australians, now feeling secure in their new base, flew in a rock band into Nui Dat on August 18. At 11:15 AM that same day, D Company left the base toward the rubber plantation at Long Tan some 2,500 meters away, reaching it at around 1 PM to relieve B Company. After having lunch together, B Company returned to base, while a small detachment of D Company left the campground to patrol the area.

An Australian soldier sweeping a banana plantation in Phuc Tuy Province, taken in 1966 before the Battle of Long Tan.

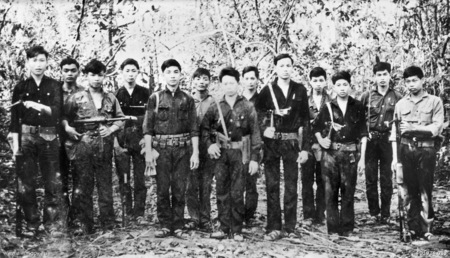

It should be understood that the VC are different from the North Vietnamese Army. The former were a guerrilla force based in South Vietnam who were sympathetic to the communist cause, many of whom wore the traditional black clothing of farmers. The NVA, however, were North Vietnamese professional soldiers who wore green uniforms.

At around 3:40 PM, the detachment came across a group of six to eight Vietnamese men wearing green uniforms. They didn’t see the Australians till Platoon Sergeant Bob Buick fired, hitting one. The rest wisely scattered.

Though the encounter was reported to base, the Australians didn’t immediately realize what they were up against. They were no longer just facing the VC 275th Regiment and the VC D445 Provincial Mobile Battalion, they were now up against at least one NVA battalion (as of 2015, the Vietnamese government remains secretive about the details).

VC soldiers of the D445 Battalion.

Shortly after resuming the advance, at 16:08 the platoon came under small-arms and rocket-propelled grenade fire from a flank after drawing ahead of the other platoons and was isolated. Pinned down, they called for artillery support as a monsoon rain began, reducing visibility.

Beginning as an encounter battle, heavy fighting ensued as the advancing battalions of the Viet Cong 275th Regiment attempted to encircle and destroy the Australians. After less than 20 minutes more than a third of 11 Platoon had become casualties, while the platoon commander was killed soon after.

Their base responded by heavily shelling the VC positions, but Air support was out of the question. Nor did those at Nui Dat want to call on the Americans. They still didn’t understand that the VC and the NVA were starting to flank D Company from different sides as they made their way toward the base.

US F-4 Phantoms over South Vietnam.

10 Platoon moved up on the left in support but was repulsed. With D Company facing a much larger force, 12 Platoon tried to push up on the right at 17:15. Fighting off an attack on their right before pushing forward another 110 yards they sustained increasing casualties after clashing with several groups moving around their western flank to form a cut-off prior to a frontal assault.

Opening a path to 11 Platoon yet unable to advance further, they threw smoke to mark their location. Nearly out of ammunition, at 18:00 two UH-1B Iroquois from No. 9 Squadron RAAF arrived overhead to resupply D Company. Meanwhile, the survivors from 11 Platoon withdrew to 12 Platoon during a lull, suffering further losses. Still heavily engaged, both platoons then moved back to the company position covered by artillery.

No. 9 Squadron RAAF Iroquois in Vietnam.

By 18:10 D Company had reformed but was still in danger of being overrun. A Company, 6 RAR was dispatched in M113 armored personnel carriers from 3 Troop, 1st APC Squadron to reinforce them. Meanwhile, B Company headquarters and one platoon were still returning to base and were also ordered to assist. Leaving Nui Dat at 17:55, the carriers moved east, crossing a swollen creek before encountering elements of D445 Battalion attempting to outflank D Company and assault it from the rear. The Viet Cong were caught by surprise as the cavalry crashed into their flank and with darkness falling they broke through while B Company entered the position at 19:00.

Arriving at a crucial point, the relief force turned the tide of the battle. The Viet Cong had been massing for another assault that would have likely destroyed D Company, yet the firepower and mobility of the armor broke their will, forcing them to withdraw. Continuing past D Company the relief force assaulted the Viet Cong, before moving back to the company position at 19:10.

The artillery had been almost constant throughout and proved critical in ensuring the survival of D Company. By 19:15 the firing had ceased and the Australians waited for another attack. However, after no counter-attack occurred they prepared to withdraw 820 yd west. With the dead and wounded loaded onto the carriers D Company left at 22:45 while B and Company departed on foot. A landing zone was then established by the cavalry with the evacuation of the casualties finally completed after midnight. Forming a defensive position ready to repulse an expected attack they remained overnight, enduring the cold and heavy rain.

Members of the Royal New Zealand Artillery (RNZA) firing an M2A2 Howitzer.

The Australians returned in strength the next day, sweeping the area and locating a large number of Viet Cong dead. Although initially believing they had suffered a major defeat, as the scale of the Viet Cong’s losses were revealed it became clear they had won a significant victory. Two wounded Viet Cong were killed after they moved to engage the Australians, while three were captured. The bodies of the missing from 11 Platoon were also located. Two men had survived despite their wounds, having spent the night in close proximity to the Viet Cong as they attempted to evacuate their own casualties.

Due to the likely presence of a sizeable force nearby the Australians remained cautious as they searched for the Viet Cong. Over the next two days, they continued to clear the battlefield, uncovering more dead as they did so. Yet with 1 ATF lacking the resources to pursue the withdrawing force, the operation ended on 21 August. Heavily outnumbered but supported by strong artillery fire, D Company held off a regimental assault before a relief force of cavalry and infantry fought their way through and forced the Viet Cong to withdraw.

Eighteen Australians were killed and 24 wounded, while the Viet Cong lost at least 245 dead which were found over the days that followed. A decisive Australian victory, Long Tan proved a major local setback for the Viet Cong, indefinitely forestalling an imminent movement against Nui Dat and establishing the task force’s dominance over the province.

Although there were other large-scale encounters in later years, 1 ATF was not fundamentally challenged again.

Australian memorial at Long Tan in 2005.

Unfortunately, Australia used the Imperial honors system, which limited the number of medals it could give out. This policy resulted in veterans receiving mere commendations, or nothing at all. This problem was finally resolved in 2008, a process that continued till 2011 when 6 RAR received a Unit Citation for Gallantry.

Update: After a 50-year campaign by Australian Vietnam veterans, the Australian government addressed the issue of awards on November 8, 2016.